Curing Poverty with Computing

Brazilian University Researchers Build Cheap

Computers for the Masses

Ben Goertzel

May 21, 2001

Brazilian computer science researcher

Wagner Meira

As we march merrily into the

cyber-infused future, armed with our PDA’s, mobile phones and superpowerful

laptops, increasingly aware of the next wave of biotech, nanotech and AI

technology about to knock us off our feet and perhaps even transport us out of

our bodies, it’s worth remembering what a small percentage of the world’s

population the cyber-revolution is currently affecting in any direct way. Even in the US, there are huge urban and

rural ghetto areas where computers are uncommon and street corner drug dealing is

a far more common teenage occupation than computer hacking. And for the majority of people in third

world countries, the technological revolution is mostly something one sees on

TV or in American or European magazines.

But it doesn’t have to be

this way. The information revolution

has the potential to benefit every human on Earth, not just those fortunate

enough to be born into certain classes or certain countries. Slowly but surely, the tech revolution is

finding its way into every corner of the planet, even into the most unlikely

and economically disadvantaged places.

On the large scale, this diffusion process may be viewed as an

inevitable consequence of the advance of technology and the overall trend of

globalization. But in practice, in

terms of nitty-gritty human reality, the expansion of technology beyond the

world’s economic elite is by no means an automatic process. Rather, it is the result of huge amounts of

hard work and careful planning by dedicated people in the growing middle classes

of developing countries. Vastly more work

will be required to finish the process of disseminating technology across class barriers, including

more cooperation from those of us in developed nations. There are technical problems involved here,

but there are also major purely human problems, with tremendously complex

political and cultural dimensions.

The individuals who are

working to improve the human condition by spreading advanced technology

throughout the human population as a whole are just as deserving of

“cyber-hero” status as the people who are working to add impressive new

functionalities to our supercomputers or mobile networks.

An excellent example of the

kind of work that’s being done to spread the technological bounty throughout

the world’s population is the recent initiative within Brazil to create a

“cheap computer for the masses.” This

project, initiated by the Brazilian government and executed by research

scientists at the Federal University of Minas Gerais in Belo Horizonte, has required

no tremendous technological innovations, but it’s been a massive effort of

coordination between government, the computer industry, and academia. Bringing computing to the masses is not

something that any of these institutions were set up to do, and carrying out

the project within this context was not an easy feat. But this is the reality within which such initiatives exist, and those who are willing and able to

cope with the tedious combination of business, technical and political issues

that such projects entail deserve our immense respect and admiration.

The importance of this

aspect of cyber-development should not be underestimated, not just in an

ethical sense but in the context of the overall course of technical and human

development. In fact, I’ll put forth a

somewhat radical proposition in this regard.

I believe that the nature of the next phase of the tech revolution will

be very different, depending on whether it really is spread across the globe or

just restricted to a small economic elite.

Technology developed within a culture of inclusion and compassion is

going to be very different from technology developed within a culture of

elitism and ethical indifference, in thousands of obvious and subtle ways. If we want our advanced technology to be

friendly and compassionate to us, we’d better develop it within a culture of

friendliness and compassion. This is

an issue that cuts at the very contradictory heart of modern cyberphilosophy,

confronting our wildest dreams and futuristic visions with the grittiest

aspects of human reality. And as we’ll

see, it’s an issue on which different contemporary cyber-visionaries take very

different views.

Brazil, A Case Study in Economic Inequity

With a 1999 GDP of $555

billion, Brazil is the tenth largest economy in the world, and is also highly

economically diverse, with huge variations in development level across

industries. Its economy history is

rocky, but the last decade has been a good one. In July 1994, led by President Fernando Enrique Cardoso, Brazil

embarked on a successful economic stabilization program, the Plano Real (named

for the new currency, the real). The

success of the plan surprised even many of its supporters. Inflation had reached an annual level of

nearly 5000% at the end of 1993, and under the Plano Real it dropped to a low

of 2.5% in 1998, climbing slightly in the years since but remaining in

single-digit range. In January 1999,

the country successfully shifted from an essentially, fixed exchange rate

regime to a floating regime. US direct

foreign investment has more than doubled since 1994, and overall trade has more

than doubled since 1990. All in all,

finally, after many years of chaos, the economy seems to be working.

In spite of this success

story, however, economic inequality in Brazil remains just about the worst – if

not the absolute worst in the world.

The standard way of measuring inequality is the Gini coefficient, which

ranges between 0 and 1: 0 if everyone in the country earns exactly the same amount;

1 if one person earns all the money and everyone else earns nothing. Throughout the 80’s and 90’s, Brazil’s Gini

coefficient has been around .60, compared to numbers in the .3-.4 range for

Southeast Asian countries, and the .4-.5 range in Africa. Latin America as a whole tends to have more

severe income inequity than most parts of the world, but even for Latin

America, Brazil is extreme: the average Gini coefficient for Argentina,

Bolivia, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Mexico, and Panama was 0.42 in the early

1990s.

|

Comparison of the Distribution of Income (Gini coefficient), Selected

Latin American Countries |

|

|

Country |

Gini Coefficient |

|

Argentina |

.49 |

|

Bolivia |

.51 |

Brazil |

.61 |

|

Chile |

.58 |

|

Colombia |

.56 |

|

Mexico |

.52 |

|

Venezuela |

.50 |

|

Source:

World Bank, Regional Study, Poverty and Policy in Latin America and the

Caribbean, Argentina Poverty Assessment and Uruguay Poverty Assessment (FYOO) |

|

What impact has the Plano

Real had on this situation? It has

drastically decreased the amount of dire poverty in Brazil, by increasing the

income level of all classes -- inarguably a very positive thing. Its impact on income distribution, however,

has been vastly less dramatic, although also significant.

There are serious human

issues here, which cannot easily be addressed by economic adjustments alone,

even extremely savvy ones as introduced by President Cardoso. The cultural divide between the Brazilian

middle class and underclass could hardly be more severe. The Brazilian middle class lives essentially

like the American or European middle class, and the Brazilian educational

system, for this small segment of the population, is outstanding. Brazil’s top universities, attended almost

entirely by middle and upper class youths, rank with the best institutions

anywhere. On the other hand, Brazil's annual expenditure

per primary school student is 12.8 times less than for its university students,

compared to a mere three-fold difference in the United States. The money that is spent on primary education

is far from equally distributed and ultimately contributes to social

inequalities in a major way.

The

drive to educate the Brazilian masses has been reasonably successful during the

past few decades. Illiteracy, which

tends to be disproportionately higher among

women, runs at 9.4 percent among Brazilian women between 30 and 39

years, but drops to 4 percent for the 15 to 19 age group. For men in the same

age groups, the rates are 11 percent and 7.9 percent, respectively. But these figures don’t tell the whole

story. There is a large gap between

basic functional literacy and having the educational background to fully

participate in the emerging global economy.

Graduating from a ghetto high school with no technical skills, no funds

to pay for commercial training school and a slim chance of getting one of the

few slots at the public universities, a typical Brazilian youth has vastly

fewer career options than someone in a similar position in a developed country. One

of the major challenges Brazil faces going forwards is to undertake reforms and

initiatives addressing the structural causes of poverty and income inequality,

and helping the country as a whole to move toward the future, as opposed to

just a small minority of privileged individuals. This is a task requiring tremendous creativity as well as money,

and one whose true dimensions will only become apparent as the work on it

unfolds.

Brazil in the Internet Era

The Brazilian software

industry is booming. The setting of the

stage for the current boom was slow and gradual. In the early 1990s, before the Plano Real, there were 100,000

people engaged in information technology activities in Brazil. Including 30,000

with advanced degrees in computer-oriented fields, 10,000 engaged in R&D

efforts, and 800 with Ph.Ds in computer science. Brazilian universities offered 210 undergraduate and 20 graduate

computer science programs, producing a steady supply of technically trained

individuals. Now, post-economic-stabilization,

the software industry is several times this size, including firms in every

aspect of computing and communications, with rapid growth in the Internet and

wireless sectors.

The Internet sector was

energized in December 1999 when Bradesco, one of the nation’s largest

commercial bank, started offering free Internet access in December 1999,

finding it could save money with online transactions and tempt advertisers with

a large captive audience. Other banks

rushed in, as did heavyweights such as UOL and Terra Networks. This has led to a burgeoning e-commerce

industry, driven more by traditional retailers than by dot-com start-ups,

although there are plenty of the latter as well. Overall, Brazilian e-commerce is expected to jump from $2.47

billion in 2000 to nearly $40 billion in 2003.

The government may lend another helping hand here, when in 2002 the

deregulation of the telecommunications market kicks in, causing a decrease in

Internet access prices and a commensurate increase in the number of Brazilians

online.

The

Brazilian wireless sector is growing at a speed exceeding even that of Europe,

let alone the relatively anemic North American wireless market. In many parts of Brazil, cell phones are a

necessity rather than a luxury. While

the situation is not as extreme nationwide as in Mexico and Venezuela, where

there are more cell phones than traditional wall phones, there are large parts

of Brazil where this may soon be the case.

According to recent Yankee Group estimates, the number of mobile users

in Brazil will increase 21 million in 2000 to 41.9 million by the end of 2003,

while the number of desktop internet users will rise from 6.1 million to 27.4

million users over the same time span.

The Brazilian Net PC – Computing for the

Masses

But how does all this

fantastic development in the Brazilian software industry affect those who live

on the wrong side of the economic divide?

The growth of wireless

technology is particularly interesting in that, more so than desktop computing,

wireless bridges class divisions. Most

of the wonderful recent growth in the Brazilian software industry affects the

underclass only through very indirect trickling-down, since few members of the

lower classes are computer users, let alone sufficiently professionally or

technically trained to participate in the information economy in any

significantly way. But, cell phones are

affordable by a much larger segment of the population than desktop computers,

and as the mobile Internet becomes a major force, wireless may be come the

major means by which high technology spreads into the depths of the Amazon and

into the sprawling, dangerous ghettos that surround every Brazilian city.

The problem with the

wireless Internet, though, is that it has very little educational value for the

user, at least as currently deployed.

It also doesn’t do much by way of expanding the user’s knowledge base,

although it does enhance career possibilities.

It is valuable in that it spreads tech-savvy thinking throughout a

larger segment of the population. And it enables communication with populations

that otherwise would have been basically inaccessible. But still, until vastly more flexibly usable

wireless devices are available, the key to enabling impoverished individuals to

participate in the tech revolution is going to be the humble and familiar

desktop PC.

This gives rise to an

obvious question. In addition to “a

chicken in every pot” (as was advertised by Franklin Delano Roosevelt in the US

during the Great Depression of the 1930’s), why not “a computer in every

home”?

One might argue that there

are more critical things to do for the Brazilian masses. Bill Gates, after he established his $21

billion Gates Foundation, quickly abandoned his initial plans to focus on

disseminating technology throughout the Third World when he realized that some

of the computers he’d donated to African villages were useless due to the

minimal availability of electricity there, and the lack of relevant education

and training. Gates decided to focus on

improving the dissemination of medicine to impoverished regions.

But, Brazil is not the Sudan

– there is very little actual starvation in Brazil at present, though there is

surely some malnutrition. Medical care

is decent by third world standards, and at its best is excellent by world

standards, although the distribution of medicine into rural regions and urban

ghettos could use much improvement, to be sure. The main problem in Brazil is not keeping people alive, but

lifting them from the cultural and material conditions of poverty and enabling

them to become full participants in the emerging global information

economy. With an Internet-connected

computer at home, a young Brazilian has the world at his fingertips, able to

learn about every topic under the sun in a self-directed way. Skills like computer programming and word

processing can also be practiced, providing the computer owner a real

possibility of participating in the new economy in a serious way.

Still, though, Brazilian minimum wage is equivalent

to roughly $90 a month, whereas a Compaq computer, for example, goes for

$1,500. So the economic obstacle to “a

computer in every home” in a Brazilian context is pretty clear.

It was with this in mind

that Joao Pimenta da Veiga Filha, Brazilian minister of communications, chose

to organize the “Net PC” project. The

idea here was to create a computer that members of the Brazilian underclass

could genuinely afford. The Net PC will

cost around $400 reiais (around US$ 200), and will be available by June

2001. Furthermore, in order to ensure

affordability, and a 24-month payment

plan will be offered.

The task of creating this

machine was turned over to the computer science department at one of Brazil’s

leading universities, the Federal University of Minas Gerais (UFMG), in Belo

Horizonte. The project was led by a

number of expert computing researchers, including Sergio Vale Aguilar Campos,

trained at Carnegie-Mellon University in the USA, and Wagner Meira, trained at

the University of Rochester in the USA.

These professors are accustomed to spending their time doing research

and teaching on advanced topics like parallel computing (running programs on

specialized computers) and automatic program verification (programs that check

to be sure other programs are doing what they’re supposed to). But they and many of their colleagues and

students were willing to take time out from this to work on the

government-sponsored project of bringing much simpler aspects of computing to a

much wider population.

The Net PC itself will be a

fairly standard one – a Pentium 500 MHz, with keyboard, mouse, 56 Kbps modem,

14" display, 64 Mb RAM and no hard disk (16 Mb flash RAM instead). According to those involved in the project,

the technical aspects of designing the system were not particularly onerous –

no major inventions or innovations were required. The hardest part was bargaining with the manufacturers of the

various parts of the machine, who tended to be oriented toward making the most

expensive and powerful machines possible rather than creating low-cost

systems.

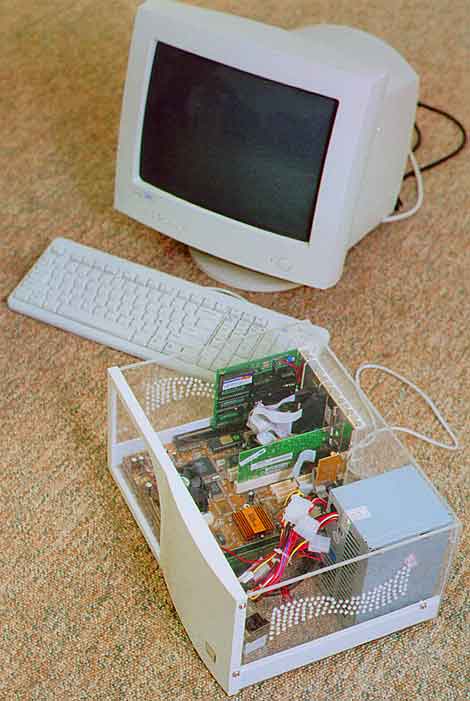

A demonstration version of the machine itself

Early on in the project it

was realized that the Microsoft Windows OS was not an option, due to its high

cost. Instead, the system was built

around the freeware Linux OS, the favorite of hackers everywhere. This is a very interesting aspect of the

project. In the US and Western Europe,

Linux is a minority OS, used by hackers, programmers and computer scientists

only. Standard tools like browsers and

word processors exist for Linux, but aren’t quite as polished or user-friendly

as on the Windows OS. On the other

hand, advanced tasks are much easier to carry out in Linux than in Windows, and

there are other major advantages, such as Linux’s increased stability (machines

running Linux can go for years without “crashing”, whereas the typical time

between crashes for Windows systems is more like days).

And Linux, unlike Windows,

is an open-source software system, meaning that anyone around the world can

edit the computer code that determines how the system runs, and make it run

differently. By its very nature, it invites

participation from users, whether those users are in the Brazilian ghetto or in

the heart of Silicon Valley. In the

same spirit as the choice of the open-source Linux architecture, the UFMG

computer scientists decided to make the

main-board architecture for the machine open as well, meaning that any

company will be able to make it, and that computer-savvy users will easily be

able to modify it or add onto it as they wish.

In fact, this is just one

example of the international move toward open-source software, which does not

yet pose a huge short-term threat to Microsoft’s hegemony in the OS market, but

may well do so in a few years time. For

instance, the government of Argentina is considering passing a new law

mandating that, after an adjustment period government offices can only use Open

Source software. And, less extremely,

the French government currently dictates that no computer files can be used in

government business unless they can be read and edited by Open Source software.

Each successive version of

Windows software uses more and more computational resources, thus providing

more functions (sometimes useful ones, sometimes useless one) and pushing

consumers to buy more and more powerful computers each year. As Wagner Meira says, in this regard the Net

PC project was strikingly contrarian.

“We did a lot of hacking for shrinking a lot of software into 16Mb. There was a lot of discussion around our

minimalist approach versus the maximalist approach usually adopted by Windows.

We are watching an ever growing and ever more flawed Windows over the years,

and our project adopted exactly the reverse direction.”

Instead of asking what can

be done to sell more software or more hardware to middle-class North Americans

(the question on the minds of most people in the US computer industry), they

asked, as Meira puts it: “What does a

computing

novice really need in a

computer? Internet (including multimedia) and text processing. Eventually software for creating a

spreadsheet or a presentation.

However,” – and here is the big difference from projects like the

American WebTV -- “the Net PC does allow expansions for those that want to have

an enhanced computing experience.”

WebTV and similar projects

allow very limited Internet use at low cost, but they don’t allow the user to

grow in sophistication. With the Net

PC, on the other hand, Meira says, “by employing an incremental approach, we

believe that we can reach a much larger portion of the population without

restricting the use of the equipment.

My mother, for instance, had a hard time to learn how to double click,

and she definitely does not know how to shut down the computer.” Yet a young Brazilian who wants to learn to

program software can do so on the Net PC; indeed its Linux kernel provides in a

some ways a better platform for this than a standard Windows-based computer.

Finally, Meira observes

cannily that the minimalist approach taken in the Net PC is the sort of thing

that could only emerge in a place like Brazil, not in a place like the USA,

where “More, more, more!” is the watchword.

“In Brazil,” he notes, “popular stuff is usually minimalist, such

as the popular car (up to 1000cc),

pre-paid cell phones, etc.” This is a

small example of the general principle that the developing world must lead its

own people into the information age.

The cultural and conceptual biases of First World countries aren’t

necessarily in synch with the needs of the rest of the world, even though First

World technology has universal applicability.

What impact will these

cheap, open-architecture computers have on the Brazilian underclass, on the

tremendous economic inequity that is the underbelly of this rapidly growing

digital economy? This remains to be

seen. One hopes that they will serve

to blur the distinction between the lower reaches of the middle class and the

upper echelons of the poor. That

families will save their money to buy cheap computers for their children, who

will then go online and learn about the depth of world far beyond their neighborhood, opening their eyes to the

possibilities that aren’t shown in TV sitcoms and reality shows. How many people, whose parents weren’t

university-educated, will use their new Net PC’s as tools to help them gain

computer skills, so that they can get in on the ground floor of one of the

software start-ups in Brazil’s booming software industry?

Of course, cheap computers

aren’t the whole solution to Brazil’s problems – they’re only one very small

piece of a huge and complicated picture.

Overall improvement of primary education in poor neighborhoods is a huge

task which is inarguably both more critical and more difficult. But it’s important not to be overwhelmed by

the magnitude of the human problems around us, and to realize that every little

bit counts. The popular bumpersticker

says “Think globally, act locally,” and this is one of those cliché’s that

actually deserves the repetition it receives.

The computer scientists at UFMG, as they take a break from their

advanced research on parallel algorithms and program verification to create inexpensive

computers for the masses, are playing an integral role in the technological

advancement of human race and the overall creation of global computational

intelligence. We need the next phase of

the tech revolution to be founded on compassion and inclusion, not elitism,

classism and egocentrism. This is a

responsibility that falls on us all.

PostScript: Class Politics and the

Cyber-visionary Community

What do the leaders of the

tech revolution in the developed world think of this kind of work? Precious few cyber-leaders are in practice

interested in devoting their time to such pursuits. One hopes that as more and more technology millionaires reach

the age where they become interested in philanthropy, the spread of the tech

revolution across the world will become a focus, along with other laudable

goals like global health and education.

But at the present time, opinions on the importance of reaching out to

the masses, and the optimal strategy for doing so, are all over the map.

A few months ago, excited

about the Brazilian Net PC and the prospect of further similar projects around

the world, hopefully coupled with serious educational initiatives, I began

talking about such things on the Extropians e-mail list, an Internet discussion

group devoted to futuristic technology and its social and economic

implications. Someone noted that the

views of the Extropian community tended not to be taken very seriously in the

mainstream press, and I suggested that, perhaps, if the Extropian community

became involved in doing something important to the mainstream world, their

opinions would be valued more. What if,

for instance, a group of Extropians devoted some of their time to education in

the Third World?

Eliezer Yudkowsky, a friend

and colleague whose opinion I respect, came down against this hard. According to him, his time and effort, and

that that of his cyber-guru colleagues, should be spent pushing

full-speed-ahead toward the “Singularity”, his word for the point at which the

acceleration of technical development becomes infinite, through computer

programs rewriting their own source code, robots rebuilding their own hardware

and other similar futuristic designs.

“How much money is spent on attempts to actually ship food directly to

the poor?” he asked. “Lots. How much

money is spent on direct efforts to implement the Singularity? … Not much.”

On the other hand, Samantha

Atkins, another Extropians list regular and a veteran Silicon Valley AI

engineer, replied to Eliezer with a different point of view: “Perhaps,” she

suggested, “there is a productive middle ground. Some of us could say more about precisely how the Singularity,

and the technologies along the way, can be applied to solving many of the

problems that beset real people right now.

We can produce and spread the memes of technology generally and AI,

nanotechnology and the Singularity in particular as answering the deepest

needs, hopes and dreams of human beings….

As part of this we also need more of a story about the steps up to

Singularity as involves the actual lives and living conditions of people. That we will muddle along somehow while a

few of the best and the brightest create a miracle is not very satisfying. What kind of world do we work toward in the

meantime? What do we do about poverty,

about technology obsoleting skills faster than new ones can be acquired, about

creating workable visions including ethics and so on? What is our attitude toward humanity?”

What is our attitude toward

humanity, indeed? Eliezer is a very

ethically serious person, and he truly believes that the best thing we in the

cyber-elite can do is for the world is to produce superior technology. The technology itself, he says, will

transform the world for everyone, and the most important thing to do is to get

the technology to this point, to the point where it can figure out how to solve

the world’s problems on its own.

There is a certain amount of

truth to this perspective. And, in my

view, there is also a certain irony to it, particularly given the fact that

Eliezer’s research so far has focused on how to make AI programs “Friendly,” in

the sense of being well-disposed toward humans. His solution to the problem of AI friendliness lies in the realm

of cognitive engineering – he believes one needs to give an AI an appropriate

goal system specifically designed to foster Friendliness.

In early 2001, I was running

the AI company Webmind Inc., and Eliezer visited our New York office to give a

lecture on Friendly AI. The lecture was

received excellently by some and terribly by others. Generally speaking the Webmind Inc. staff were absorbed with the

practical problems of trying to create real digital intelligence, whereas

Eliezer was more concerned with the various philosophical and futuristic issues

that will arise once a truly intelligent AI system is completed. But the issue of “wiring in Friendliness”

definitely struck everyone powerfully, one way or another. Among the milder responses, one of our

Brazilian software engineers – not one of the several who had worked on the Net

PC project before joining Webmind, but a good friend of those who had, and a

student of Wagner Meira and Sergio Campos – raised his hand and politely said:

“But perhaps the most important thing is not the in-built goal system, but

whether we teach it by example.” The

friendlier we are, in other words, the friendlier our AI systems are going to

be.

The issue is clear and

poignant. What the Brazilian engineer

was suggesting was that, if our superhuman AI grows up watching us act as

though most humans are dispensable and irrelevant, perhaps it will, in its

adulthood, believe that we too are dispensable and irrelevant. On the other hand, perhaps, as Eliezer says,

it will grow up and understand that building it was the best thing the

cyber-elite could do for humanity as a whole, and it will then proceed to

spread joy and plenty throughout the land.

Who knows?

These rarefied ethical

disputes are fascinating, but they easily carry one away into the domain of

angels dancing on the heads of pins. And this is why the kind of work done by Campos, Meira and their

colleagues is so intriguing. There’s no

arguing with the real physical-world power of millions of impoverished

Brazilians logging onto the Net and discovering discussion groups like Extropians,

where things like ethics and technology are discussed, and speculations on

superhuman AI appears alongside critiques of the latest Java release. Without the Net PC and other things like it,

these people might well never get to log on and argue with Eliezer for

themselves. (Not, at any rate, unless

the Singularity comes fast enough that superhuman AI systems revolutionize

their lives before they get old.)

In spite of the success of

Cardoso’s economic reforms, there is a lot of justified skepticism in Brazil

about the whole political system and everything the government does. University people are up in arms over

Cardoso’s plan to charge significant university tuition, breaking a tradition

of free university education for all sufficiently academically distinguished

students. As Thiago Turchetti Maia,

another Brazilian software engineer and student of Meira and Campos, says, “You

know the money saved from charging tuition is not going to go to send poor

people to university. You know it’s

just going to disappear.” But when

asked about the Net PC project, he waxes at least a bit more positive.. “Well,

there, you can see what the money’s going towards,” he says. ”At least that’s something real.” He shrugs.

“Maybe it will make some difference….”